Jupiter Trojan

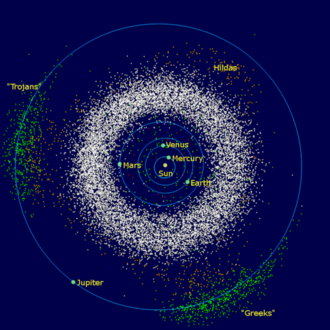

The Jupiter Trojans, commonly called Trojans or Trojan asteroids, are a large group of objects that share the orbit of the planet Jupiter around the Sun. Relative to Jupiter, each Trojan librates around one of the planet's two Lagrangian points of stability, Template:L4 and Template:L5, that respectively lie 60° ahead of and behind the planet in its orbit. Trojan asteroids are distributed in two elongated, curved regions around these Lagrangian points with an average semi-major axis of about 5.2 AU.[1]

The first Trojan, 588 Achilles, was discovered in 1906 by the German astronomer Max Wolf.[2] A total of 2,909 Jupiter Trojans have been found Template:As of.[3] The name "Trojans" derives from the fact that, by convention, they each are named after a mythological figure from the Trojan War. The total number of Jupiter Trojans larger than 1 km is believed to be about 1 million, approximately equal to the number of asteroids larger than 1 km in the main asteroid belt.[1] Like main belt asteroids, Trojans form families.[4]

Jupiter Trojans are dark bodies with reddish, featureless spectra. No firm evidence of the presence of water, organic matter or other chemical compounds has been obtained. The Trojans' densities (as measured by studying binaries or rotational lightcurves) vary from 0.8 to 2.5 g·cm−3.[4] Trojans are thought to have been captured into their orbits during the early stages of the Solar System's formation or slightly later, during the migration of giant planets.[4]

Observational history

In 1772, Italian-born mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, in his studies of the restricted three-body problem, predicted that a small body sharing an orbit with a planet but lying 60° ahead or behind it will be trapped near these points.[2] The trapped body will librate slowly around the exact point of equilibrium in a tadpole or horseshoe orbit.[5] These leading and trailing points are called the Template:L4 and Template:L5 Lagrange points,[6] respectively.[Note 1] However, subsequent to Lagrange's hypothesis, no asteroids trapped in Lagrange points were observed for more than a century. Those around Jupiter were the first to be found.[2]

E. E. Barnard made the first recorded observation of a Trojan asteroid, Template:Mpl, in 1904, but the significance of his observation was not noted at the time.[7] Barnard believed he saw the recently discovered Saturnian satellite Phoebe, which was only two arc-minutes away in the sky at the time, or possibly a star. The object's identity was not realised until its orbit was constructed in 1999.[7]

The first true discovery of a Trojan occurred in February 1906, when astronomer Max Wolf of Heidelberg-Königstuhl State Observatory discovered an asteroid at the Template:L4 Lagrangian point of the Sun–Jupiter system, later named 588 Achilles.[2] In 1906–1907 two more Jupiter Trojans were found by fellow German astronomer August Kopff (624 Hektor and 617 Patroclus).[2] Hektor, like Achilles, belonged to the Template:L4 swarm, while Patroclus was the first asteroid known to reside at the Template:L5 Lagrangian point.[8] By 1938, 11 Trojans had been detected.[9] This number only increased to 14 by 1961.[2] Template:As of, there are 1,634 known Trojan asteroids at Template:L4 and 1,277 at Template:L5,[10] but the rate of discovery is growing rapidly as instruments improve: in January 2000, a total of 257 had been discovered;[6] by May 2003, that number had grown to 1,600.[11]

Nomenclature

The custom of naming all asteroids in Jupiter's Template:L4 and Template:L5 points after famous heroes of the Trojan War was suggested by Johann Palisa of Vienna, who was the first to accurately calculate their orbits.[2] Asteroids in the Template:L4 group are named after Greek heroes (the "Greek node or camp" or "Achilles group"), and those at the Template:L5 point are named after the heroes of Troy (the "Trojan node or camp").[2] Confusingly, 617 Patroclus was named before the Greece/Troy rule was devised, and a Greek name thus appears in the Trojan node; the Greek node also has one "misplaced" asteroid, 624 Hektor, named after a Trojan hero.[9]

The term "Trojan" also is used to refer to other small Solar System bodies with similar relationships to larger bodies: for example, there are both Mars Trojans and Neptune Trojans, and Saturn has Trojan moons.[Note 2]

Numbers and mass

Estimates of the total number of Trojans are based on deep surveys of limited areas of the sky.[1] The Template:L4 swarm is believed to hold between 160–240,000 asteroids with diameters larger than 2 km and 600,000 with diameters larger than 1 km.[1][6] If the Template:L5 swarm contains a comparable number of objects, there are more than 1 million Trojans. These numbers are similar to that of comparable asteroids in the main asteroid belt.[1] The total mass of the Trojans is estimated at 0.0001 of the mass of Earth or one-fifth of the mass of the main asteroid belt.[6] The number of Trojans probably is known completely for those of absolute magnitude 9.0–9.5.[4] The number of Trojans observed in the Template:L4 swarm is slightly larger than that observed in Template:L5; however, since the brightest Trojans show little variation in numbers between the two populations, this disparity is probably due to an observational bias.[4] However some models indicate that the Template:L4 swarm may be slightly more stable than the Template:L5 swarm.[5]

The largest of the Trojans is 624 Hektor, which has an average radius of 101.5 ± 1.8 km.[11] There are few large Trojans in comparison to the overall population. The number of Trojans grows very quickly with decreasing size down to 84 km, much more so than in the main asteroid belt. The 84 km diameter corresponds to an absolute magnitude of 9.5, assuming an albedo of 0.04. Within the 4.4–40 km range the Trojans' size distribution resembles that of the main belt asteroids. An absence of data means that nothing is known about the masses of the smaller Trojans.[5] This distribution suggests that the smaller Trojans are the products of collisions by larger Trojans.[4]

Orbits

The Jupiter Trojans have orbits with radii in between 5.05 AU and 5.35 AU (mean semi-major axis is 5.2 ± 0.15 AU), and are distributed throughout elongated, curved regions around the two Lagrangian points;[1] each swarm stretches for about 26° along the orbit of Jupiter, amounting to a total distance of about 2.5 AU.[6] The width of the swarms approximately equals two Hill's radii, which in the case of Jupiter amounts to about 0.6 AU.[5] Many of Jupiter's Trojans have large orbital inclinations relative to the orbital plane of the planet—up to 40°.[6]

The Trojans do not maintain a fixed separation from Jupiter. They slowly librate around their respective equilibrium points, periodically moving closer to Jupiter or further from it.[5] Trojans generally follow paths called tadpole orbits around the Lagrangian points; the average period of their libration is about 150 years.[6] The amplitude of the libration (along the Jovian orbit) varies from 0.6° to 88°, with the average being about 33°.[5] Simulations showed that Trojans can follow even more complicated trajectories when moving from one Lagrangian point to another—these are called horseshoe orbits (currently no Jupiter Trojan with such an orbit is known).[5]

Dynamical families and binaries

Discerning dynamical families within the Trojan population is more difficult than it is in the asteroid belt, because the Trojans are locked within a far narrower range of possible positions than the main belt asteroids. This means that clusters tend to overlap and merge with the overall swarm. However, as of 2003 roughly a dozen dynamical families have been identified within the Trojans. Trojan families are much smaller in size than families in the main belt; the largest identified family, the Menelaus group, consists of only eight members.[4]

Only one Trojan binary asteroid, 617 Patroclus, has been identified to date. The binary's orbit is extremely close, at 650 km, compared to 35,000 km for the primary's Hill sphere.[13] The largest Trojan asteroid—624 Hektor—likely is a contact binary too.[4][14]

Physical properties

Jupiter Trojans are dark bodies of irregular shape. Their geometric albedos generally vary between 3 and 10%.[11] The average value is 0.056 ± 0.003.[4] The asteroid 4709 Ennomos has the highest albedo (0.18) of all Trojans.[11] Little is known about the masses, chemical composition, rotation or other physical properties of the Trojans.[4]

Rotation

The rotational properties of Trojans are not well known. Analysis of the rotational light curves of 72 Trojan asteroids gave an average rotational period of about 11.2 hours, whereas the average period of the control sample of the main belt asteroids was 10.6 hours.[15] The distribution of the rotational periods of Trojans appeared to be well approximated by a Maxwellian function,[Note 3] whereas the similar distribution of main belt asteroids was found to be non-Maxwellian with a deficit of asteroids with periods in the range 8–10 hours.[15] The Maxwellian distribution of the rotational periods of Trojans may indicate that they have undergone a stronger collisional evolution compared to the main belt.[15]

However in 2008 a team from Calvin College analyzed the light curves of a debiased sample of ten Trojans, and found a median spin period of 18.9 hours. This value was significantly lower than the value for main belt asteroids of similar size (11.5 hours). The difference could mean that the Trojans possess a lower average density, which may imply that they formed in the Kuiper belt (see below).[16]

Composition

Spectroscopically, the Jupiter Trojans mostly are D-type asteroids, which predominate in the outer regions of the main belt.[4] A small number are classified as P or C-type asteroids.[15] Their spectra are red (meaning that they reflect light at longer wavelengths) or neutral and featureless.[11] No firm evidence of water, organics or other chemical compounds has been obtained Template:As of, though 4709 Ennomos has an albedo slightly higher than the Trojan average, which may indicate the presence of water ice. In addition, a number of other Trojans, such as 911 Agamemnon and 617 Patroclus, have shown very weak absorptions at 1.7 and 2.3 μm, which might indicate the presence of organics.[17] The Trojans' spectra are similar to those of the irregular moons of Jupiter and, to certain extent, comet nuclei, though Trojans are spectrally very different from the redder Kuiper belt objects.[1][4] A Trojan's spectrum can be matched to a mixture of water ice, a large amount of carbon-rich material (charcoal),[4] and possibly magnesium-rich silicates.[15] The composition of the Trojan population appears to be markedly uniform, with little or no differentiation between the two swarms.[18]

A team from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii announced in 2006 that it had measured the density of the binary Trojan asteroid 617 Patroclus as being less than that of water ice (0.8 g/cm3), suggesting that the pair, and possibly many other Trojan objects, more closely resemble comets or Kuiper belt objects in size and composition—water ice with a layer of dust—than they do the main belt asteroids.[13] Countering this argument, the density of Hektor as determined from its rotational lightcurve (2.480 g/cm3) is significantly higher than that of 617 Patroclus.[14] Such a difference in densities is puzzling and indicates that density may not be a good indicator of asteroid origin.[14]

Origin and evolution

Two main theories have emerged to explain the formation and evolution of the Trojans. The first suggests that the Trojans formed in the same part of the Solar System as Jupiter and entered their orbits while the planet was forming.[5] The last stage of Jupiter's formation involved runaway growth of its mass through the accretion of large amounts of hydrogen and helium from the protoplanetary disk; during this growth, which lasted for only about 10,000 years, the mass of Jupiter increased by a factor of ten. The planetesimals that had approximately the same orbits as Jupiter were caught by the increased gravity of the planet.[5] The capture mechanism was very efficient—about 50% of all remaining planetesimals were trapped. This hypothesis has two major problems: the number of trapped bodies exceeds the observed population of Trojans by four orders of magnitude, and the present Trojan asteroids have larger orbital inclinations than are predicted by the capture model.[5] However, simulations of this scenario show that such a mode of formation also would inhibit the creation of similar Trojans around Saturn, and this has been born out by observation: to date no Trojans have been found around Saturn.[19]

The second theory, part of the Nice model, proposes that the Trojans were captured during planetary migration, which happened about 500–600 million years after the Solar System's formation.[20] The migration was triggered by the passage of Jupiter and Saturn through the 1:2 mean motion resonance. During it Uranus, Neptune and to some extent Saturn moved outward, while Jupiter moved slightly inward.[20] Migrating giant planets destabilized the primordial Kuiper belt throwing millions of objects into the inner Solar System. In addition, their combined gravitational influence quickly would have disturbed any pre-existing Trojans.[20] Under this theory, the present Trojan population eventually accumulated from those runaway Kuiper belt objects as Jupiter and Saturn moved away from the resonance.[21]

The long-term future of the Trojans is open to question, as multiple weak resonances with Jupiter and Saturn cause them to behave chaotically over time.[22] In addition, collisional shattering slowly depletes the Trojan population as fragments are ejected. Ejected Trojans could become temporary satellites of Jupiter or Jupiter family comets.[4] Simulations show that up to 17% of Jupiter's Trojans are unstable over the age of the Solar System, and so must have been ejected from their orbits at some time before now.[23] Levison et al. believe that roughly 200 ejected Trojans greater than 1 km in diameter might be traveling the Solar System, with a few possibly on Earth-crossing orbits.[24] Some of the escaped Trojans may become Jupiter family comets as they approach the Sun and their surface ice begins evaporating.[24]

See also

- List of Trojan asteroids (Greek camp)

- List of Trojan asteroids (Trojan camp)

- Pronunciation of Trojan asteroid names

- List of objects at Lagrangian points

- List of Jupiter-crossing minor planets

- Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

Notes

- ↑ The three other points—Template:L1, Template:L2 and Template:L3—are unstable.[5]

- ↑ Simulations suggest Saturn and Uranus have few if any Trojans.[12] The term "Trojan asteroid" is normally understood to specifically mean the Jupiter Trojans since the first Trojans were discovered near Jupiter's orbit and Jupiter currently has by far the most known Trojans.[3]

- ↑ The Maxwellian function is , where is the average rotational period, is the dispersion of periods.

References

Template:Source list Template:Source list Template:Reflist

External links

Template:Jupiter Template:Small Solar System bodies

be-x-old:Траянскі астэроід ca:Asteroide troià cs:Troján da:Trojanske asteroider de:Trojaner (Astronomie) es:Asteroide troyano fr:Astéroïde troyen ko:트로이 소행성군 hr:Trojanski asteroid it:Asteroidi troiani di Giove lb:Trojaner (Astronomie) nl:Trojanen-planetoïden ja:トロヤ群 no:Jupitertrojan nn:Jupitertrojan pl:Trojańczycy pt:Asteroide troiano ru:Троянские астероиды simple:Trojan asteroid sk:Trójan (planétka) sl:Trojanski asteroid fi:Troijalainen asteroidi sv:Trojanerna tr:Troyalı göktaşları zh:特洛伊小行星

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedYoshida2005 - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNicholson1961 - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJewitt2004 - ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMarzari2002 - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJewitt2000 - ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEinarsson1913 - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWyse1938 - ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFernandes2003 - ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMarchis2006 - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLacerda2007 - ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBarucci2002 - ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLevison2007 - ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedRobutal2005 - ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Template:Cite journal